Navigating Files and Directories

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

How can I move around the cluster filesystem

How can I see what files and directories I have?

How can I make new files and directories.

Objectives

Create, edit, manipulate and remove files from command line

Translate an absolute path into a relative path and vice versa.

Use options and arguments to change the behaviour of a shell command.

Demonstrate the use of tab completion and explain its advantages.

The Unix Shell

This episode will be a quick introduction to the Unix shell, only the bare minimum required to use the cluster.

The Software Carpentry ‘Unix Shell’ lesson covers the subject in more depth, we recommend you check it out.

The part of the operating system responsible for managing files and directories is called the file system. It organizes our data into files, which hold information, and directories (also called ‘folders’), which hold files or other directories.

Understanding how to navigate the file system using command line is essential for using an HPC.

Directories are like places — at any time while we are using the shell, we are in exactly one place called our current working directory. Commands mostly read and write files in the current working directory, i.e. ‘here’, so knowing where you are before running a command is important.

First, let’s find out where we are by running the command pwd for ‘print working directory’.

[yourUsername@mahuika ~]$ pwd

/home/<username>

The output we see is what is known as a ‘path’. The path can be thought of as a series of directions given to navigate the file system.

At the top is the root directory that holds all the files in a filesystem.

We refer to it using a slash character, /, on its own.

This is what the leading slash in /home/<username> is referring to, it is telling us our path starts at the root directory.

Next is home, as it is the next part of the path we know it is inside the root directory,

we also know that home is another directory as the path continues.

Finally, stored inside home is the directory with your username.

The NeSI filesystem looks something like this:

The directories that are relevant to us are.

| Location | Default Storage | Default Files | Backup | Access Speed | |

| Home is for user-specific files such as configuration files, environment setup, source code, etc. | /home/<username> |

20GB | 1,000,000 | Daily | Normal |

| Project is for persistent project-related data, project-related software, etc. | /nesi/project/<projectcode> |

100GB | 100,000 | Daily | Normal |

| Nobackup is a 'scratch space', for data you don't need to keep long term. Old data is periodically deleted from nobackup | /nesi/nobackup/<projectcode> |

10TB | 1,000,000 | None | Fast |

Managing your data and storage (backups and quotas)

NeSI performs backups of the /home and /nesi/project (persistent) filesystems. However, backups are only captured once per day. So, if you edit or change code or data and then immediately delete it, it likely cannot be recovered. Note, as the name suggests, NeSI does not backup the /nesi/nobackup filesystem.

Protecting critical data from corruption or deletion is primarily your

responsibility. Ensure you have a data management plan and stick to the plan to reduce the chance of data loss. Also important is managing your storage quota. To check your quotas, use the nn_storage_quota command, eg

$ nn_storage_quota

Quota Location Available Used Use% State Inodes IUsed IUse% IState

home_johndoe 20G 14.51G 72.57% OK 1000000 112084 11.21% OK

project_nesi99991 100G 101G 101.00% LOCKED 100000 194 0.19% OK

nobackup_nesi99991 10T 0 0.00% OK 1000000 14 0.00% OK

As well as disk space, ‘inodes’ are also tracked, this is the number of files.

Notice that the project space for this user is over quota and has been locked, meaning no more data can be added. When your space is locked you will need to move or remove data. Also note that none of the nobackup space is being used. Likely data from project can be moved to nobackup. nn_storage_quota uses cached data, and so will no immediately show changes to storage use.

For more details on our persistent and nobackup storage systems, including data retention and the nobackup autodelete schedule, please see our Filesystem and Quota documentation.

Version Control

Version control systems (such as Git) often have free, cloud-based offerings (e.g., BitBucket, GitHub and GitLab) that are generally used for storing source code. Even if you are not writing your own programs, these can be very useful for storing job submit scripts, notes and other files. Git is not an appropriate solution for storing data.

Slashes

Notice that there are two meanings for the

/character. When it appears at the front of a file or directory name, it refers to the root directory. When it appears inside a path, it’s just a separator.

As you may now see, using a bash shell is strongly dependent on the idea that your files are organized in a hierarchical file system. Organizing things hierarchically in this way helps us keep track of our work: it’s possible to put hundreds of files in our home directory, just as it’s possible to pile hundreds of printed papers on our desk, but it’s a self-defeating strategy.

Listing the contents of directories

To list the contents of a directory, we use the command ls followed by the path to the directory whose contents we want listed.

We will now list the contents of the directory we we will be working from. We can use the following command to do this:

[yourUsername@mahuika ~]$ ls /nesi/nobackup/nesi99991

introhpc2403

You should see a directory called introhpc2403, and possibly several other directories. For the purposes of this workshop you will be working within /nesi/nobackup/nesi99991/introhpc2403

Command History

You can cycle through your previous commands with the ↑ and ↓ keys. A convenient way to repeat your last command is to type ↑ then enter.

lsReading ComprehensionWhat command would you type to get the following output

original pnas_final pnas_sub

ls pwdls backupls /Users/backupls /backupSolution

- No:

pwdis not the name of a directory.- Possibly: It depends on your current directory (we will explore this more shortly).

- Yes: uses the absolute path explicitly.

- No: There is no such directory.

Moving about

Currently we are still in our home directory, we want to move into theproject directory from the previous command.

The command to change directory is cd followed by the path to the directory we want to move to.

The cd command is akin to double clicking a folder in a graphical interface.

We will use the following command:

[yourUsername@mahuika ~]$ cd /nesi/nobackup/nesi99991/introhpc2403

You will notice that cd doesn’t print anything. This is normal. Many shell commands will not output anything to the screen when successfully executed.

We can check we are in the right place by running pwd.

[yourUsername@mahuika ~]$ pwd

/nesi/nobackup/nesi99991/introhpc2403

Creating directories

As previously mentioned, it is general useful to organise your work in a hierarchical file structure to make managing and finding files easier. It is also is especially important when working within a shared directory with colleagues, such as a project, to minimise the chance of accidentally affecting your colleagues work. So for this workshop you will each make a directory using the mkdir command within the workshops directory for you to personally work from.

[yourUsername@mahuika ~]$ mkdir <username>

You should then be able to see your new directory is there using ls.

[yourUsername@mahuika ~]$ ls /nesi/nobackup/nesi99991/introhpc2403

array_sum.r usr123 usr345

General Syntax of a Shell Command

We are now going to use ls again but with a twist, this time we will also use what are known as options, flags or switches.

These options modify the way that the command works, for this example we will add the flag -l for “long listing format”.

[yourUsername@mahuika ~]$ ls -l /nesi/nobackup/nesi99991/introhpc2403

-rw-r-----+ 1 usr9999 nesi99991 460 Nov 18 17:03

-rw-r-----+ 1 usr9999 nesi99991 460 Nov 18 17:03 array_sum.r

drwxr-sr-x+ 3 usr9999 nesi99991 4096 22 Sep 08:40 birds

drwxrws---+ 2 usr123 nesi99991 4096 Nov 15 09:01 usr123

drwxrws---+ 2 usr345 nesi99991 4096 Nov 15 09:01 usr345

We can see that the -l option has modified the command and now our output has listed all the files in alphanumeric order, which can make finding a specific file easier.

It also includes information about the file size, time of its last modification, and permission and ownership information.

Most unix commands follow this basic structure.

The prompt tells us that the terminal is accepting inputs, prompts can be customised to show all sorts of info.

The command, what are we trying to do.

Options will modify the behavior of the command, multiple options can be specified.

Options will either start with a single dash (-) or two dashes (--)..

Often options will have a short and long format e.g. -a and --all.

Arguments tell the command what to operate on (usually files and directories).

Each part is separated by spaces: if you omit the space

between ls and -l the shell will look for a command called ls-l, which

doesn’t exist. Also, capitalization can be important.

For example, ls -s will display the size of files and directories alongside the names,

while ls -S will sort the files and directories by size.

Another useful option for ls is the -a option, lets try using this option together with the -l option:

[yourUsername@mahuika ~]$ ls -la

drwxrws---+ 4 usr001 nesi99991 4096 Nov 15 09:00 .

drwxrws---+ 12 root nesi99991 262144 Nov 15 09:23 ..

-rw-r-----+ 1 cwal219 nesi99991 460 Nov 18 17:03 array_sum.r

drwxrws---+ 2 usr123 nesi99991 4096 Nov 15 09:01 usr123

drwxrws---+ 2 usr345 nesi99991 4096 Nov 15 09:01 usr345

Single letter options don’t usually need to be separate. In this case ls -la is performing the same function as if we had typed ls -l -a.

You might notice that we now have two extra lines for directories . and ... These are hidden directories which the -a option has been used to reveal, you can make any file or directory hidden by beginning their filenames with a ..

These two specific hidden directories are special as they will exist hidden inside every directory, with the . hidden directory representing your current directory and the .. hidden directory representing the parent directory above your current directory.

Exploring More

lsFlagsYou can also use two options at the same time. What does the command

lsdo when used with the-loption? What about if you use both the-land the-hoption?Some of its output is about properties that we do not cover in this lesson (such as file permissions and ownership), but the rest should be useful nevertheless.

Solution

The

-loption makeslsuse a long listing format, showing not only the file/directory names but also additional information, such as the file size and the time of its last modification. If you use both the-hoption and the-loption, this makes the file size ‘human readable’, i.e. displaying something like5.3Kinstead of5369.

Relative paths

You may have noticed in the last command we did not specify an argument for the directory path. Until now, when specifying directory names, or even a directory path (as above), we have been using what are know absolute paths, which work no matter where you are currently located on the machine since it specifies the full path from the top level root directory.

An absolute path always starts at the root directory, which is indicated by a

leading slash. The leading / tells the computer to follow the path from

the root of the file system, so it always refers to exactly one directory,

no matter where we are when we run the command.

Any path without a leading / is a relative path.

When you use a relative path with a command

like ls or cd, it tries to find that location starting from where we are,

rather than from the root of the file system.

In the previous command, since we did not specify an absolute path it ran the command on the relative path from our current directory

(implicitly using the . hidden directory), and so listed the contents of our current directory.

We will now navigate to the parent directory, the simplest way do do this is to use the relative path ...

[yourUsername@mahuika ~]$ cd ..

We should now be back in /nesi/nobackup/nesi99991.

[yourUsername@mahuika ~]$ pwd

/nesi/nobackup/nesi99991

Two More Shortcuts

The shell interprets a tilde (

~) character at the start of a path to mean “the current user’s home directory”. For example, if Nelle’s home directory is/home/nelle, then~/datais equivalent to/home/nelle/data. This only works if it is the first character in the path:here/there/~/elsewhereis nothere/there//home/nelle/elsewhere.Another shortcut is the

-(dash) character.cdwill translate-into the previous directory I was in, which is faster than having to remember, then type, the full path. This is a very efficient way of moving back and forth between two directories – i.e. if you executecd -twice, you end up back in the starting directory.The difference between

cd ..andcd -is that the former brings you up, while the latter brings you back.

Absolute vs Relative Paths

Starting from

/home/amanda/data, which of the following commands could Amanda use to navigate to her home directory, which is/home/amanda?

cd .cd /cd home/amandacd ../..cd ~cd homecd ~/data/..cdcd ..Solution

- No:

.stands for the current directory.- No:

/stands for the root directory.- No: Amanda’s home directory is

/home/amanda.- No: this command goes up two levels, i.e. ends in

/home.- Yes:

~stands for the user’s home directory, in this case/home/amanda.- No: this command would navigate into a directory

homein the current directory if it exists.- Yes: unnecessarily complicated, but correct.

- Yes: shortcut to go back to the user’s home directory.

- Yes: goes up one level.

Relative Path Resolution

Using the filesystem diagram below, if

pwddisplays/Users/thing, what willls ../backupdisplay?

../backup: No such file or directory2012-12-01 2013-01-08 2013-01-27original pnas_final pnas_sub

Solution

- No: there is a directory

backupin/Users.- No: this is the content of

Users/thing/backup, but with.., we asked for one level further up.- Yes:

../backup/refers to/Users/backup/.

Clearing your terminal

If your screen gets too cluttered, you can clear your terminal using the

clearcommand. You can still access previous commands using ↑ and ↓ to move line-by-line, or by scrolling in your terminal.

Listing in Reverse Chronological Order

By default,

lslists the contents of a directory in alphabetical order by name. The commandls -tlists items by time of last change instead of alphabetically. The commandls -rlists the contents of a directory in reverse order. Which file is displayed last when you combine the-tand-rflags? Hint: You may need to use the-lflag to see the last changed dates.Solution

The most recently changed file is listed last when using

-rt. This can be very useful for finding your most recent edits or checking to see if a new output file was written.

Globbing

One of the most powerful features of bash is filename expansion, otherwise known as globbing. This allows you to use patterns to match a file name (or multiple files), which will then be operated on as if you had typed out all of the matches.

*is a wildcard, which matches zero or more characters.Consider a directory containing the following files

kaka.txt kakapo.jpeg kea.txt kiwi.jpeg pukeko.jpegThe pattern

ka*will matchkaka.txtandkakapo.jpegas these both start with “ka”. Where as*.jpegwill matchkakapo.jpeg,kiwi.jpegandpukeko.jpegas they all end in “.jpeg”k*a.*will match justkaka.txtandkea.txt

?is also a wildcard, but it matches exactly one character.

????.*would returnkaka.txtandkiwi.jpeg.When the shell sees a wildcard, it expands the wildcard to create a list of matching filenames before running the command that was asked for. As an exception, if a wildcard expression does not match any file, Bash will pass the expression as an argument to the command as it is. However, generally commands like

wcandlssee the lists of file names matching these expressions, but not the wildcards themselves. It is the shell, not the other programs, that deals with expanding wildcards.

List filenames matching a pattern

Running

lsin a directory gives the outputcubane.pdb ethane.pdb methane.pdb octane.pdb pentane.pdb propane.pdbWhich

lscommand(s) will produce this output?

ethane.pdb methane.pdb

ls *t*ane.pdbls *t?ne.*ls *t??ne.pdbls ethane.*Solution

The solution is

3.

1.shows all files whose names contain zero or more characters (*) followed by the lettert, then zero or more characters (*) followed byane.pdb. This givesethane.pdb methane.pdb octane.pdb pentane.pdb.

2.shows all files whose names start with zero or more characters (*) followed by the lettert, then a single character (?), thenne.followed by zero or more characters (*). This will give usoctane.pdbandpentane.pdbbut doesn’t match anything which ends inthane.pdb.

3.fixes the problems of option 2 by matching two characters (??) betweentandne. This is the solution.

4.only shows files starting withethane..

include in terminal excersise (delete slurm files later on maybe?)

Tab completion

Sometimes file paths and file names can be very long, making typing out the path tedious. One trick you can use to save yourself time is to use something called tab completion. If you start typing the path in a command and their is only one possible match, if you hit tab the path will autocomplete (until there are more than one possible matches).

Solution

For example, if you type:

[yourUsername@mahuika ~]$ cd intand then press Tab (the tab key on your keyboard), the shell automatically completes the directory name for you (since there is only one possible match):

[yourUsername@mahuika ~]$ cd introhpc2403/However, you want to move to your personal working directory. If you hit Tab once you will likely see nothing change, as there are more than one possible options. Hitting Tab a second time will print all possible autocomplete options.

cwal219/ riom/ harrellw/Now entering in the first few characters of the path (just enough that the possible options are no longer ambiguous) and pressing Tab again, should complete the path.

Now press Enter to execute the command.

[yourUsername@mahuika ~]$ cd introhpc2403/<username>Check that we’ve moved to the right place by running

pwd./nesi/nobackup/nesi99991/introhpc2403/<username>

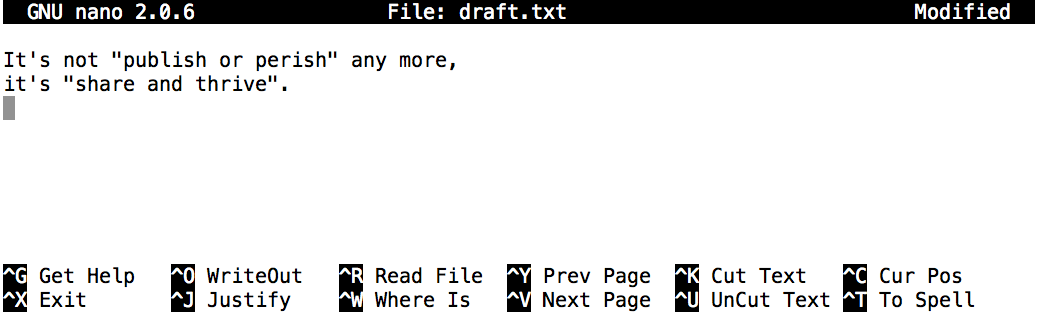

Create a text file

Now let’s create a file. To do this we will use a text editor called Nano to create a file called draft.txt:

[yourUsername@mahuika ~]$ nano draft.txt

Which Editor?

When we say, ‘

nanois a text editor’ we really do mean ‘text’: it can only work with plain character data, not tables, images, or any other human-friendly media. We use it in examples because it is one of the least complex text editors. However, because of this trait, it may not be powerful enough or flexible enough for the work you need to do after this workshop. On Unix systems (such as Linux and macOS), many programmers use Emacs or Vim (both of which require more time to learn), or a graphical editor such as Gedit. On Windows, you may wish to use Notepad++. Windows also has a built-in editor callednotepadthat can be run from the command line in the same way asnanofor the purposes of this lesson.No matter what editor you use, you will need to know where it searches for and saves files. If you start it from the shell, it will (probably) use your current working directory as its default location. If you use your computer’s start menu, it may want to save files in your desktop or documents directory instead. You can change this by navigating to another directory the first time you ‘Save As…’

Let’s type in a few lines of text.

Once we’re happy with our text, we can press Ctrl+O

(press the Ctrl or Control key and, while

holding it down, press the O key) to write our data to disk

(we’ll be asked what file we want to save this to:

press Return to accept the suggested default of draft.txt).

Once our file is saved, we can use Ctrl+X to quit the editor and return to the shell.

Control, Ctrl, or ^ Key

The Control key is also called the ‘Ctrl’ key. There are various ways in which using the Control key may be described. For example, you may see an instruction to press the Control key and, while holding it down, press the X key, described as any of:

Control-XControl+XCtrl-XCtrl+X^XC-xIn nano, along the bottom of the screen you’ll see

^G Get Help ^O WriteOut. This means that you can useControl-Gto get help andControl-Oto save your file.

nano doesn’t leave any output on the screen after it exits,

but ls now shows that we have created a file called draft.txt:

[yourUsername@mahuika ~]$ ls

draft.txt

Copying files and directories

In a future lesson, we will be running the R script /nesi/nobackup/nesi99991/introhpc2403/array_sum.r, but as we can’t all work on the same file at once you will need to take your own copy. This can be done with the copy command cp, at least two arguments are needed the file (or directory) you want to copy, and the directory (or file) where you want the copy to be created. We will be copying the file into the directory we made previously, as this should be your current directory the second argument can be a simple ..

[yourUsername@mahuika ~]$ cp /nesi/nobackup/nesi99991/introhpc2403/array_sum.r .

We can check that it did the right thing using ls

[yourUsername@mahuika ~]$ ls

draft.txt array_sum.r

Other File operations

mv to move move a file, is used similarly to cp taking a source argument(s) and a destination argument.

rm will remove move a file and only needs one argument.

The mv command is also used to rename a file, for example mv my_fiel my_file. This is because as far as the computer is concerned moving and renaming a file are the same operation.

In order to cp a directory (and all its contents) the -r for recursive option must be used.

The same is true when deleting directories with rm

| command | name | usage |

|---|---|---|

cp |

copy | cp file1 file2 |

cp -r directory1/ directory2/ |

||

mv |

move | mv file1 file2 |

mv directory1/ directory2/ |

||

rm |

remove | rm file1 file2 |

rm -r directory1/ directory2/ |

For mv and cp if the destination path (final argument) is an existing directory the file will be placed inside that directory with the same name as the source.

Moving vs Copying

When using the

cporrmcommands on a directory the ‘recursive’ flag-rmust be used, butmvdoes not require it?Solution

We mentioned previously that as far the computer is concerned, renaming is the same operation as moving. Contrary to what the commands name implies, all moving is actually renaming. The data on the hard drive stays in the same place, only the label applied to that block of memory is changed. To copy a directory, each individual file inside that directory must be read, and then written to the copy destination. To delete a directory, each individual file in the directory must be marked for deletion, however when moving a directory the files inside are the data inside the directory is not interacted with, only the parent directory is “renamed” to a different place.

This is also why

mvis faster thancpas no reading of the files is required.

Unsupported command-line options

If you try to use an option (flag) that is not supported,

lsand other commands will usually print an error message similar to:$ ls -jls: invalid option -- 'j' Try 'ls --help' for more information.

Getting help

Commands will often have many options. Most commands have a --help flag, as can be seen in the error above. You can also use the manual pages (aka manpages) by using the man command. The manual page provides you with all the available options and their use in more detail. For example, for thr ls command:

[yourUsername@mahuika ~]$ man ls

Usage: ls [OPTION]... [FILE]...

List information about the FILEs (the current directory by default).

Sort entries alphabetically if neither -cftuvSUX nor --sort is specified.

Mandatory arguments to long options are mandatory for short options, too.

-a, --all do not ignore entries starting with .

-A, --almost-all do not list implied . and ..

--author with -l, print the author of each file

-b, --escape print C-style escapes for nongraphic characters

--block-size=SIZE scale sizes by SIZE before printing them; e.g.,

'--block-size=M' prints sizes in units of

1,048,576 bytes; see SIZE format below

-B, --ignore-backups do not list implied entries ending with ~

-c with -lt: sort by, and show, ctime (time of last

modification of file status information);

with -l: show ctime and sort by name;

otherwise: sort by ctime, newest first

-C list entries by columns

--color[=WHEN] colorize the output; WHEN can be 'always' (default

if omitted), 'auto', or 'never'; more info below

-d, --directory list directories themselves, not their contents

-D, --dired generate output designed for Emacs' dired mode

-f do not sort, enable -aU, disable -ls --color

-F, --classify append indicator (one of */=>@|) to entries

... ... ...

To navigate through the man pages,

you may use ↑ and ↓ to move line-by-line,

or try B and Spacebar to skip up and down by a full page.

To search for a character or word in the man pages,

use / followed by the character or word you are searching for.

Sometimes a search will result in multiple hits. If so, you can move between hits using N (for moving forward) and Shift+N (for moving backward).

To quit the man pages, press Q.

Manual pages on the web

Of course, there is a third way to access help for commands: searching the internet via your web browser. When using internet search, including the phrase

unix man pagein your search query will help to find relevant results.GNU provides links to its manuals including the core GNU utilities, which covers many commands introduced within this lesson.

Key Points

The file system is responsible for managing information on the disk.

Information is stored in files, which are stored in directories (folders).

Directories can also store other directories, which then form a directory tree.

cd [path]changes the current working directory.

ls [path]prints a listing of a specific file or directory;lson its own lists the current working directory.

pwdprints the user’s current working directory.

cp [file] [path]copies [file] to [path]

mv [file] [path]moves [file] to [path]

rm [file]deletes [file]

/on its own is the root directory of the whole file system.Most commands take options (flags) that begin with a

-.A relative path specifies a location starting from the current location.

An absolute path specifies a location from the root of the file system.

Directory names in a path are separated with

/on Unix, but\on Windows.

..means ‘the directory above the current one’;.on its own means ‘the current directory’.